Rising seas, devastating cyclones, ferocious storm surges.

Scientists have long predicted climate change could pose an existential threat to the tiny island nations which dot the Pacific.

But it’s not just the region’s natural geography in peril — its political geography could be endangered as well.

Pacific leaders are worried rising seas could wreak havoc with maritime boundaries throughout the region.

Now Pacific officials and experts have gathered to try to come up with an answer to a difficult question:

What will they do if the markers they’ve used to trace sweeping boundaries across vast stretches of ocean slowly disappear beneath the waves?

What’s the problem?

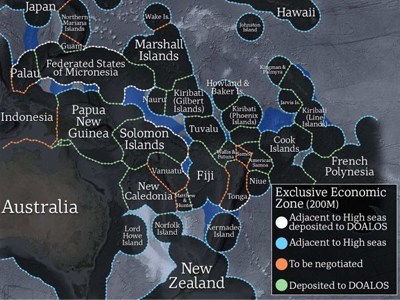

Most Pacific Islands might only be tiny specks of land, but they’re the custodians of vast oceans.

The nation of Tuvalu, for example, is made up of a string of tiny atolls which are only 26 square kilometres in total.

But its ocean territories cover more than 900,000 square kilometres — slightly larger than the state of New South Wales.

The Cook Islands add up to 600 square kilometres of dry land, but it oversees a vast ocean territory of about 2 million square kilometres.

Determining who owns what in this huge aquatic realm hasn’t been easy.

Maritime boundaries are normally pegged to isolated shards of land — islands, atolls, reefs and rocks which barely poke above sea level.

But Josh Mitchell from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the nation of Cook Islands says his nation is worried rising seas could soon swamp many of these crucial markers.

“A warming climate means melting polar caps. And the consequence of that is sea level rise,” he said.

“You generate these maritime jurisdiction areas from areas of land. If you lose that land does that consequently mean you lose the maritime jurisdiction that is generated from it?

“That’s the question we’re looking at.”

He’s not the only one asking.

There’s more at stake here than just water

The economic consequences are very real.

Maritime boundaries determine who has the right to Pacific fisheries worth more than $3 billion — a huge sum for a region with few sources of income.

It is not the first time Pacific nations find themselves at the pointy end of a global problem, and mapping out a solution will take years, not months.

Mr Mitchell is optimistic about the future, but says the region must hammer out a lasting and peaceful solution.

“There’s no question that economically and comparatively speaking we have far more to lose than most other countries,” he said.

“There’s a lot more riding on it for us. That’s why we’re here. We need to work this out.”

The existing laws are old

Mr Mitchell is one of 63 officials and experts from around the Pacific who have gathered at Sydney University this week to discuss the issue.

It’s a modest meeting, but it could mark a seminal moment in the Pacific.

While technical experts and scientists in the region have had detailed discussions about maritime borders and climate change, this is the first time officials have begun the laborious process of sketching out a political solution.

And they’re working on a canvas which is largely blank.

The foundation document for the current maritime boundaries — the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea — was written in 1982, when the prospect of rising seas seemed distant.

“The law of the sea didn’t really contemplate climate change or sea level in any meaningful way,” Mr Mitchell said. “It is largely silent.”

Why don’t they freeze the current boundaries?

That’s certainly one option. The nations could agree to simply fix existing survey points on the map — even if they do disappear under water in the future.

But there are also several contested borders in the Pacific.

Predicting how climate change will affect those negotiations is difficult.

Some Pacific leaders might spot an advantage in the shifting seascape which might help them to press their claims.

Experts say it will be easier for politicians to resist that temptation if the whole region can come up with a set of principles to govern how governments deal with an increasingly fluid map.

The talks at Sydney University have been organised by the Pacific Community, which provides technical and scientific advice to countries across the region.

Its deputy director-general, Dr Audrey Aumua, says she hopes Pacific leaders will prize collaboration over contestation.

“The spirt with which the Pacific has worked to achieve the current goals of maritime boundaries success has been the principle of cooperation,” she said.

“I think for the Pacific this is an important principle, and I think they’d maintain that.”

Published: ABC- Pacific Beat